For Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, memory is not merely recollection but a living organism: a drumbeat echoing through generations, storing traces of experience, knowledge, and imagination. He describes this phenomenon as a ‘memory drum,’ an inner mechanism that gathers and transmits the essence of life, much like genetic inheritance. This idea unfolds in his artistic practice, where form and abstraction become vessels of shared memory and collective identity.

This interview is an excerpt from issue #74 Being Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim where the artist talks to Selections about his understanding of memory and its manifestation in his work.

Anastasia Nysten (A.N): Can you explain your piece called Memory Drum to me?

Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim (M.I): Yes. Every person has it. Just as the drum on an old piano stores the memory of a tune, so there is something in us that accumulates our experience. Only, with humans, this accumulates from the day we’re born. As you get older, you start to get some of the earlier stuff back. I can retrieve my childhood memories from that place in the brain. A person is full of this knowledge, this treasure, and it becomes a legacy. It turns into genes and is inherited. In the generation that follows it might reappear. It’s like eye colour. One of my children has very dark eyes. He carries the genes of the previous generation. In the same way, the cognitive and visual store of one generation turns into a form of heritage.

A.N: Can you give me an example of any of your works that demonstrate this idea?

M.I: All of my work demonstrates it. Of course, in some cases the inspiration is more specific. Sometimes a particular sentence or a poem affects me.

A.N: Your exhibition at the Venice Biennale, Between Sunrise and Sunset, was a huge achievement. It resembles human forms and nature at the same time. Was this intended, or did you just see it that way?

M.I: That exhibition was a heavy burden. I felt I had to speak on behalf of my community, not just myself. Venice is so important in the art world. The geography of the UAE is two bays, one facing the Gulf of Oman and the Indian Ocean, the other the Arab Gulf. We live between these two bays in many different natural environments, with different customs and dialects. We’re very diverse. I wanted to convey the nature of this demography.

A.N: And what about the similarities between humans and animals? Does this mean anything or not?

M.I: It does mean something, because I intentionally created a shape – let’s say, a figurative shape – and I’m not the first one to do that. Compare the way Piet Mondrian saw a tree and started representing it, or how he represented an apple. It’s not a mystery, like I said before. It’s just that, in the most abstract form, I’m trying to minimise the shape. When you reach the smallest form, it creates a different position for the viewer. It gives that viewer freedom. If they see a tree, that’s fine. If they see a man or a woman, it’s equally true. There is no wrong answer. So, there’s a lot of room for the viewer to see it in a different way. It carries all the meanings that the viewer can come up with.

A.N: What was the importance of the role of artistic value, of Maya Allison, in shaping the ultimate vision for the exhibition?

M.I: Maya Allison is someone I respect a lot. I often work with her. I respect her opinion. The problem is that the art space – especially in the modern era, because of the existence of technology – has become vast, and the artist’s freedom has become greater. This creates so many concepts. To be honest, I don’t agree with the classification of artistic works into schools, for example, because I see this as coming from the critics, to facilitate their study of artistic works.

ISSUE #74

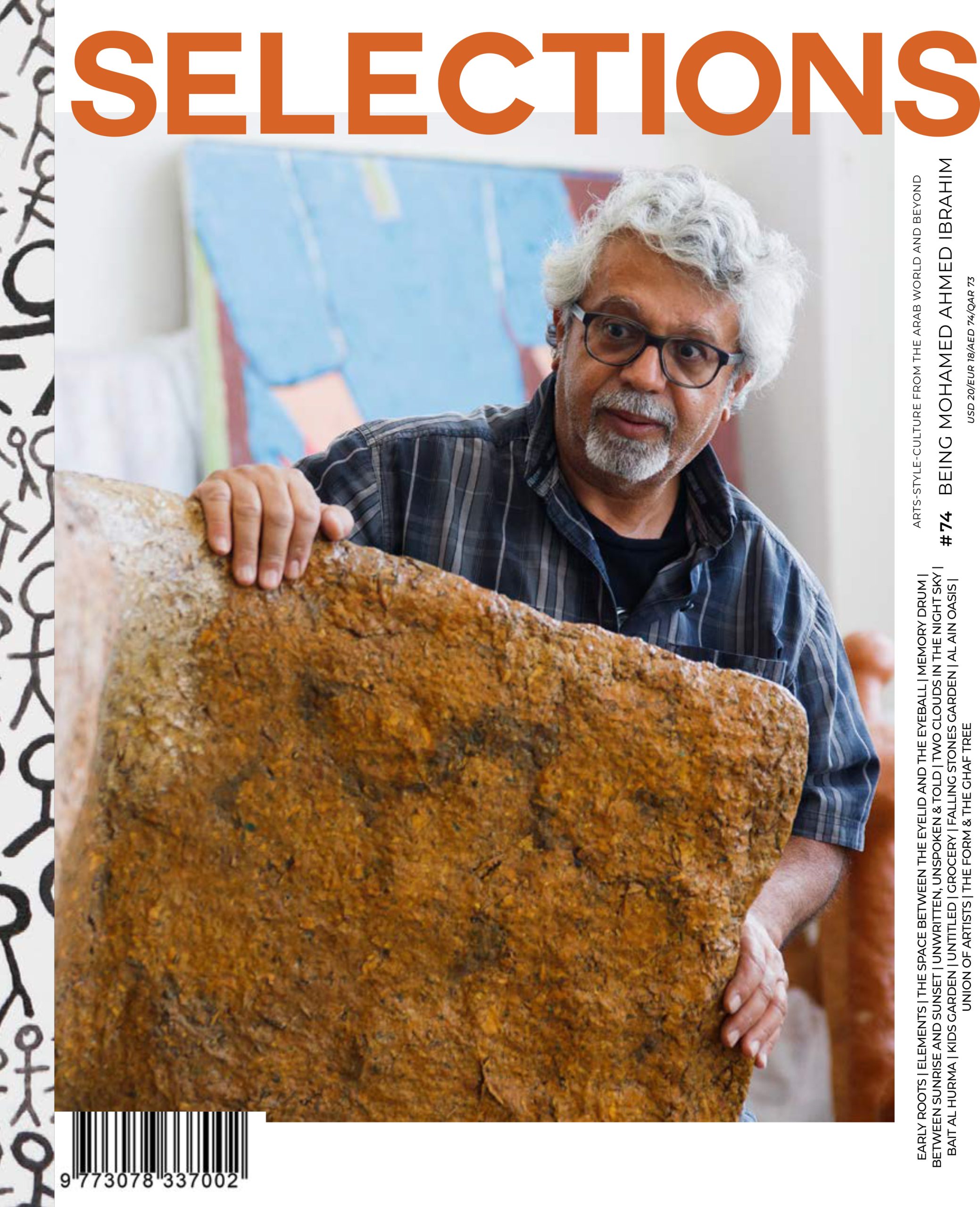

Selections’ issue #74 Being Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim traces the life and practice of Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, an artist whose vividly coloured, repeating forms carry both playfulness and depth. Emerging in a period when the UAE had little contemporary art infrastructure, Ibrahim helped shape an early experimental community alongside a small circle of peers, building a language rooted in persistence and imagination rather than institutional support.

The publication follows his journey from these formative years to major international recognition, including Desert X AlUla (2020), the UAE Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2022), and works entering the Guggenheim collection (2024). At its core, the issue presents Ibrahim’s work as an enduring meditation on colour, repetition, landscape, and joy as a serious artistic pursuit. Get your copy here.