To curate is to care, for ideas, for artists, for audiences. Yet today, curating extends far beyond exhibition-making. It has evolved into a civic act, a form of cultural mediation that bridges histories, geographies, and communities. This evolution is particularly vivid in regions like the Gulf, where cultural investments have reshaped the global art landscape and inspired new models of artistic dialogue.

As guest curator for Art Here 2025 and the Richard Mille Art Prize at Louvre Abu Dhabi, I have witnessed firsthand how curatorship can serve as a form of custodianship, not only of objects and narratives, but of the relationships that shape meaning. To be a custodian curator is to hold space for dialogue, to protect the integrity of artistic voices, and to translate cultural nuance for diverse publics.

The Rise of the Cultural Mediator

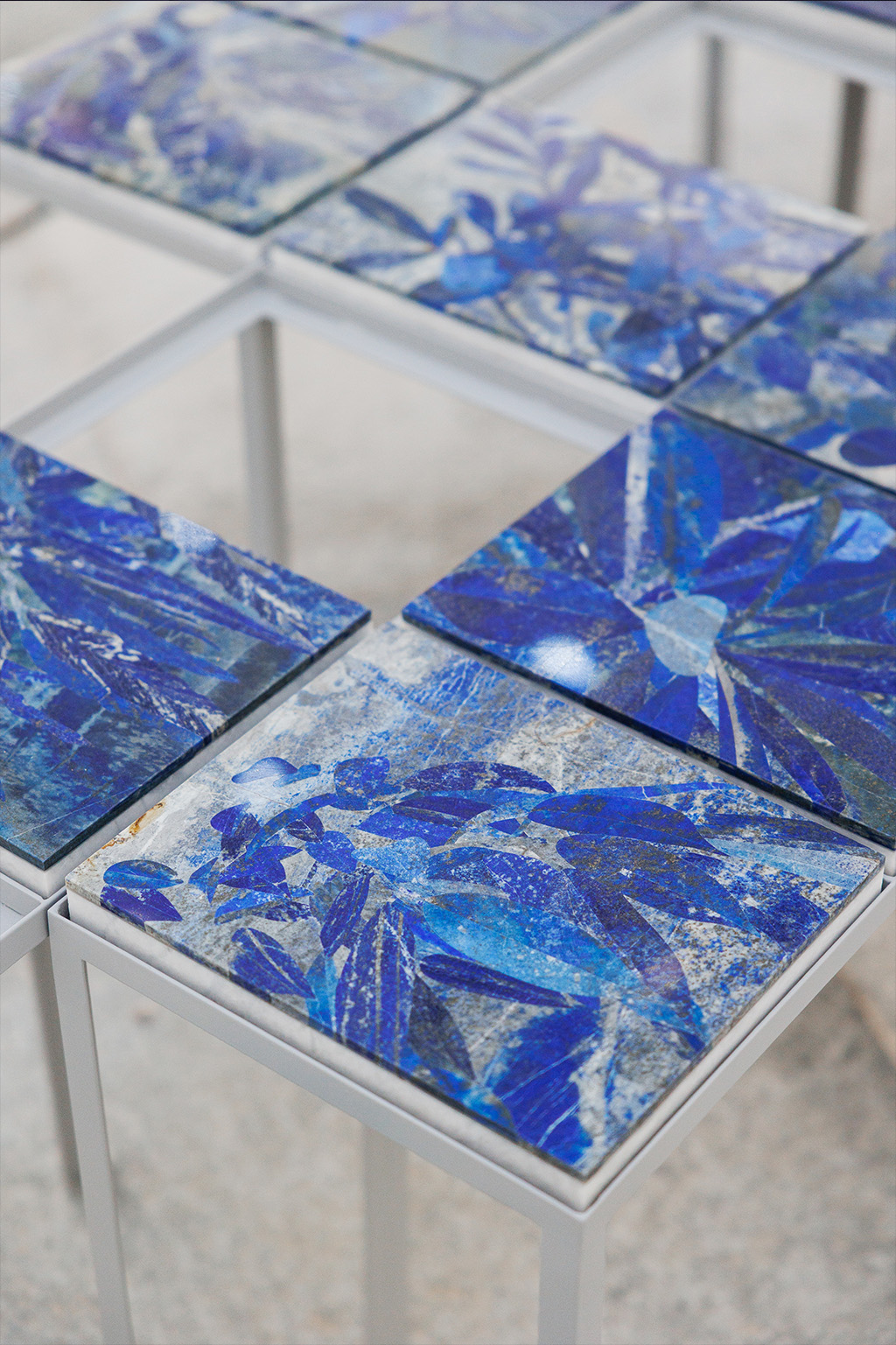

In today’s interconnected art world, the role of the curator increasingly resembles that of a cultural ambassador. We are not only responsible for selecting works and organising exhibitions; we also represent, interpret, and sometimes defend the contexts in which those works exist. When working in cross-cultural environments, as in Art Here 2025, which brought together artists from Japan and the Arab world, this mediating role becomes essential.

For the participating Japanese artists, some of whom were visiting the UAE and the wider Arab region for the first time, the experience was transformative. During installation days, my role extended far beyond logistics. I became a translator, linguistically, culturally, and emotionally, helping bridge understanding between the artists and diverse audiences. Those exchanges demonstrated how artistic practice itself can become a form of cultural exchange, rooted in curiosity and respect.

Shifts in the Curator’s Role

The curator’s role is gradually evolving. Once viewed primarily as scholarly or administrative, it now extends to include public engagement, advocacy, and representation. Curators are often expected to maintain a public presence, articulate institutional values, and embody the spirit of the exhibitions they create.

This shift mirrors broader social and cultural transformations. Around the world and particularly in the Gulf, governments and cultural institutions have invested heavily in building new museums, biennials, and art fairs. These spaces not only showcase art but also serve as instruments of cultural diplomacy and platforms for cross-cultural understanding.

The Gulf’s contemporary art movement, which has been growing for over two decades, is now at a moment of flourishing visibility. These developments are not just regional phenomena; they are part of a global realignment that recognises the multiplicity of art histories and voices. For curators, this means working within new frameworks, ones that are often governmentally driven but deeply collaborative to foster a balance between local authenticity and international resonance.

Custodianship in Practice

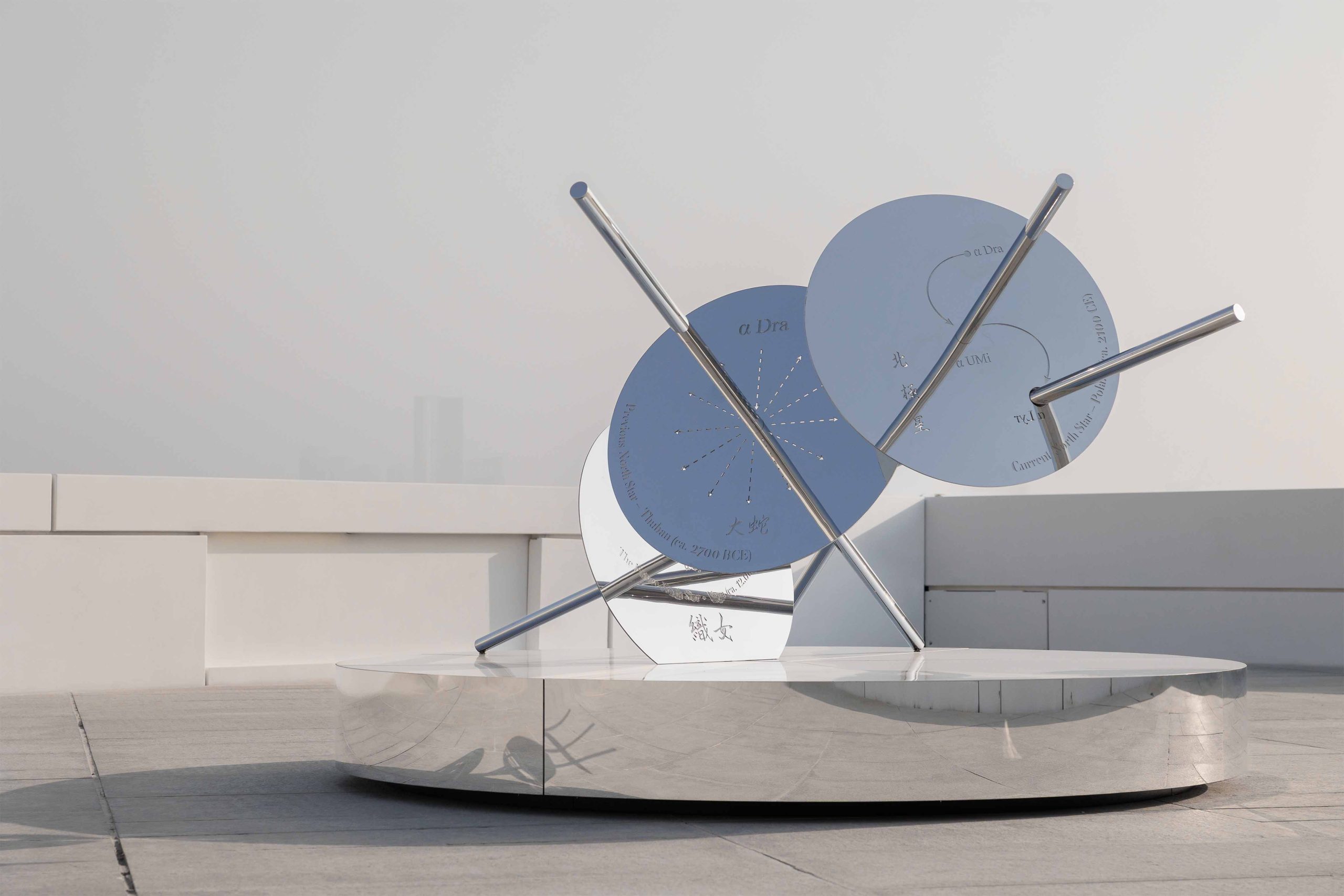

To act as a custodian curator is to engage deeply with context. At Louvre Abu Dhabi, the museum’s mission of seeing humanity in a new light offers an extraordinary foundation for this work. Each edition of the Art Here and the Richard Mille Art Prize invites a new guest curator to interpret the museum’s spaces and themes through a contemporary lens, shaping an Art Here exhibition that reflects both local realities and global artistic dialogues.

This approach requires trust, collaboration, and intellectual openness. It’s a chance for curators to work closely with artists in the process of creation, from initial concept to final installation, while ensuring that the exhibition becomes a platform for dialogue rather than just display.

In my case, my background in art history has been central to this process. I was fortunate to study under mentors whose guidance shaped both my regional and global outlook, from the late Tarek Al-Ghoussein, who introduced me to the UAE’s contemporary art scene, and Salwa Mikdadi, who emphasised the value of the living archive, to Mia M. Mochizuki, whose approach to comparative art history informs how I think about curation in a poly-centric world.

Curating as Civic Duty

Ultimately, I see curating as a form of civic duty, a service not only to artists and audiences, but to society at large. Large-scale exhibitions, biennials, and public art initiatives have the power to create beauty, inspire empathy, and spark connections across divides. In a fragmented world, they can help us find meaning and hope.

The curator’s role, then, is not simply to assemble artworks, but to weave relationships: between cultures, between disciplines, between the past and the present. Custodianship is about care, not ownership, and about the humility to listen as much as to speak.

As the art world continues to evolve, curators must embrace this expanded role, as mediators, translators, and stewards of shared imagination. Only then can we truly serve the purpose of art: to illuminate, to connect, and to remind us of our collective humanity.

About Sophie Mayuko Arni

Sophie Mayuko Arni is a Swiss-Japanese independent curator based between the UAE and Japan. Her curatorial practice spans public art, site-specific exhibitions, and digital publishing, with a focus on connecting the Gulf and Japan through shared themes of heritage, architecture, futurism, and ecology. As Founding Editor of Global Art Daily, she archives Arab and Asian contemporary art in global dialogue. Arni initiated the “East-East: UAE meets Japan” series (2016–) and has curated projects for Louvre Abu Dhabi, Noor Riyadh, and The Third Line. She holds a BA from NYU Abu Dhabi and an MPhil from Tokyo University of the Arts.